Formative assessment, developmental stages and starting the year well

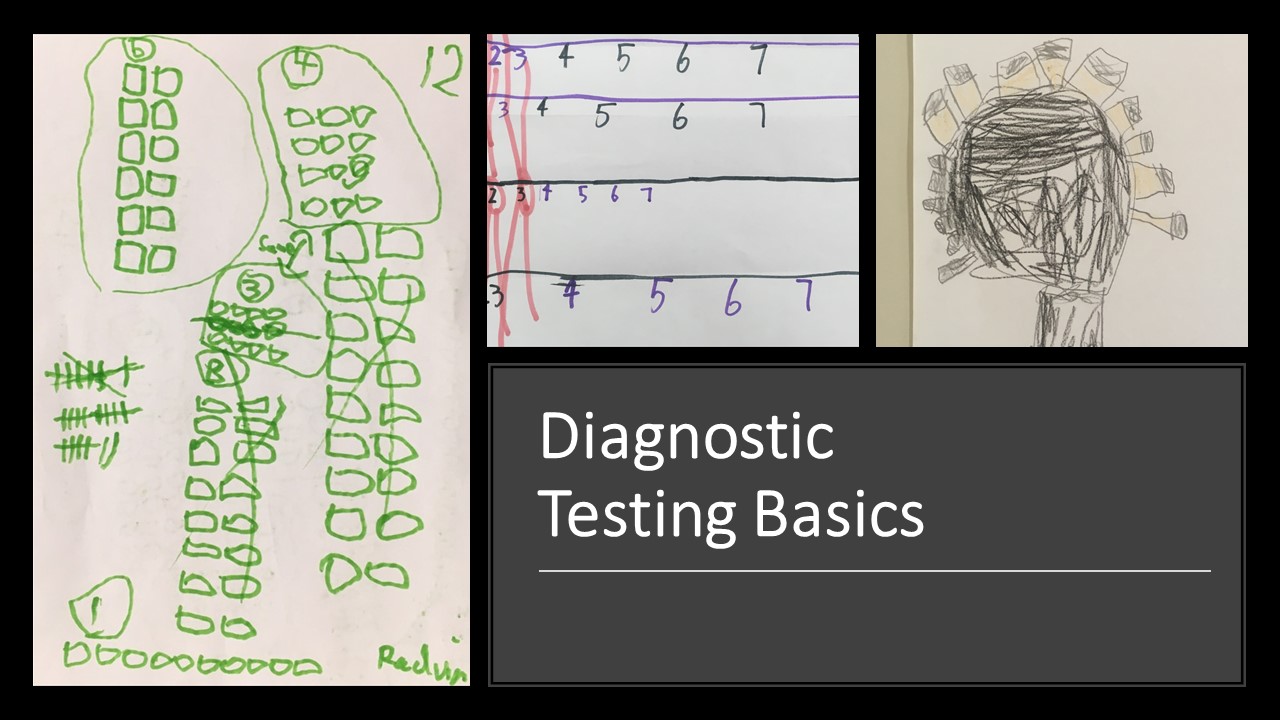

The goal of formative assessment should always be to find out what each student NEEDS next, rather than focusing

>>> Why does intervention look so very different to what we would consider to be great maths?

Intervention is hard. The Masters Report (2009) shows that there is a gap of 2.5 years between the lowest and highest performing 20% of students by year five. And that grows to more than five years by year nine.

In fact, the report claims that often when kids are behind by the end of primary school, they never catch up.

It is disturbing – horrifying really – that by the end of primary school some kids’ life options are already significantly impaired by their lack of mathematical understanding.

What disturbs me even more, and it is honestly one of the biggest traps that we can fall into when dealing with struggling kids, is that it is tempting to abandon our most effective teaching methods in an attempt to make it “easier” for the kids.

Even when we know that challenging problems are great for helping kids to think deeply about maths, develop more connections and improve overall results, we tend to shy away from using them with struggling students. In fact, Australian research by Peter Sullivan shows that teachers tend to reduce the complexity in challenging tasks as soon as they think kids might struggle. If we do that, when will kids who are struggling with maths get a chance to actually solve problems?

And here lies the paradox…

We use great maths and challenging tasks with our top kids to push them to develop stronger understanding… yet for kids who are struggling we take away those opportunities in favour of more detailed explanations and the practicing of skills.

Our top kids get accelerated, but our strugglers are never given those same brain-growing opportunities. Doesn’t that seem wrong? Surely, intervention should consist of the best maths possible, not avoiding all mathematical thinking in favour of arithmetic.

I understand that this can be a confronting thought for many teachers. It is instinctively difficult to see a student struggling and yet continue to push them to struggle more. I find it useful to remind myself that those students are the ones who most need to achieve the deep understanding that only comes from discovering for themselves the relationships, patterns and rules that underpin mathematical thought. Kids can learn – really! One of the most exciting parts of my job is hearing from teachers who have had kids become deeply curious and engaged in maths.

Let’s give struggling kids truly great maths – brain growing maths, challenging maths – then they will close the gaps, catch up, and exceed the expectations of those around them.

Great intervention, is great maths.

Want more?

The goal of formative assessment should always be to find out what each student NEEDS next, rather than focusing

Recently I’ve been pondering findings from a major report into Australian schooling that kids who are struggling in maths by

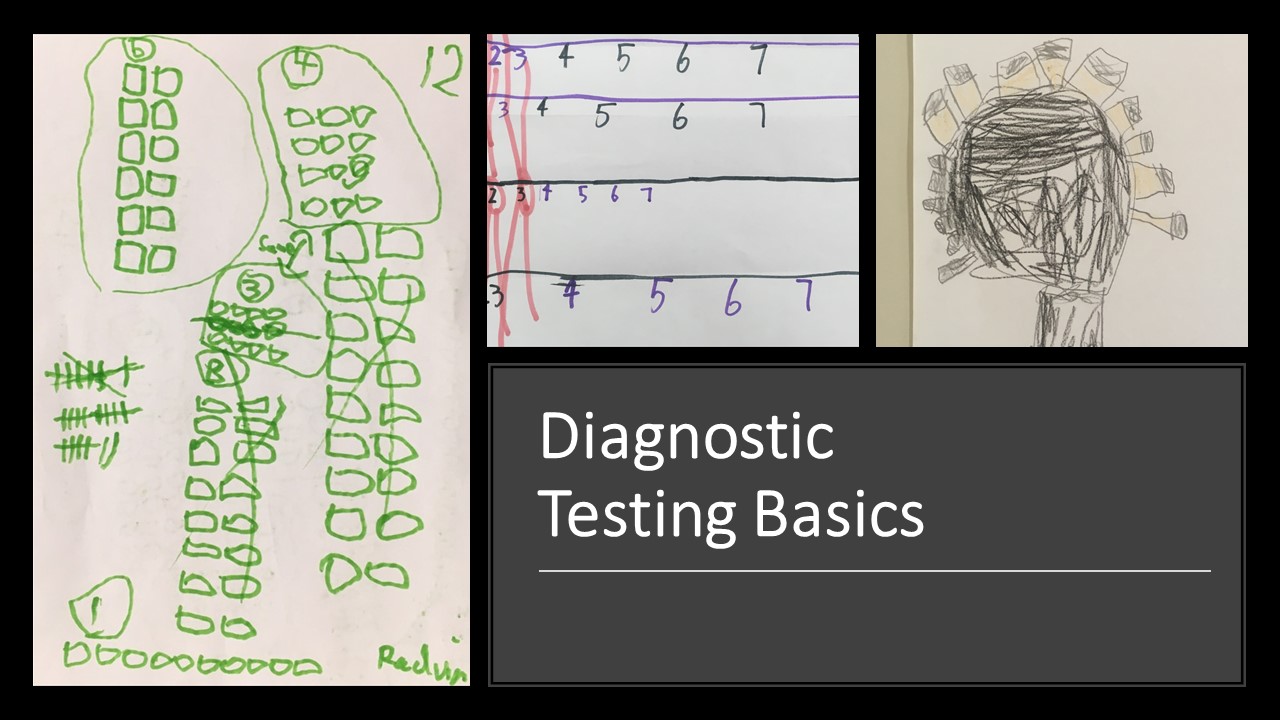

Enabling prompts or life lines are a fantastic way of helping students who are stuck to get started. They do not reduce

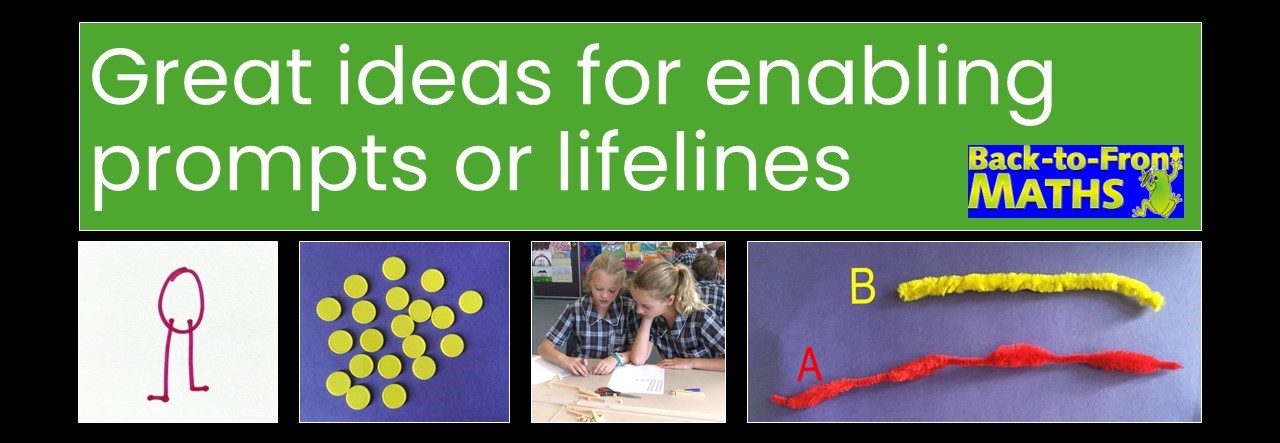

Pie charts are an awesome way of linking statistics, fractions and angles, however they can often be difficult for students

While it may sound counter-intuitive, the easiest way to learn to tell the time is to remove the minute hand

Hundreds charts are great for connecting tens and ones. Why not turn one into a jigsaw puzzle to use in

KENNEDY PRESS PTY LTD

FOR ALL ENQUIRIES, ORDERS AND TO ARRANGE PD:

© COPYRIGHT 2023 KENNEDY PRESS PTY LTD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TERMS & CONDITIONS